Tommy Papaioannou – August 2016.

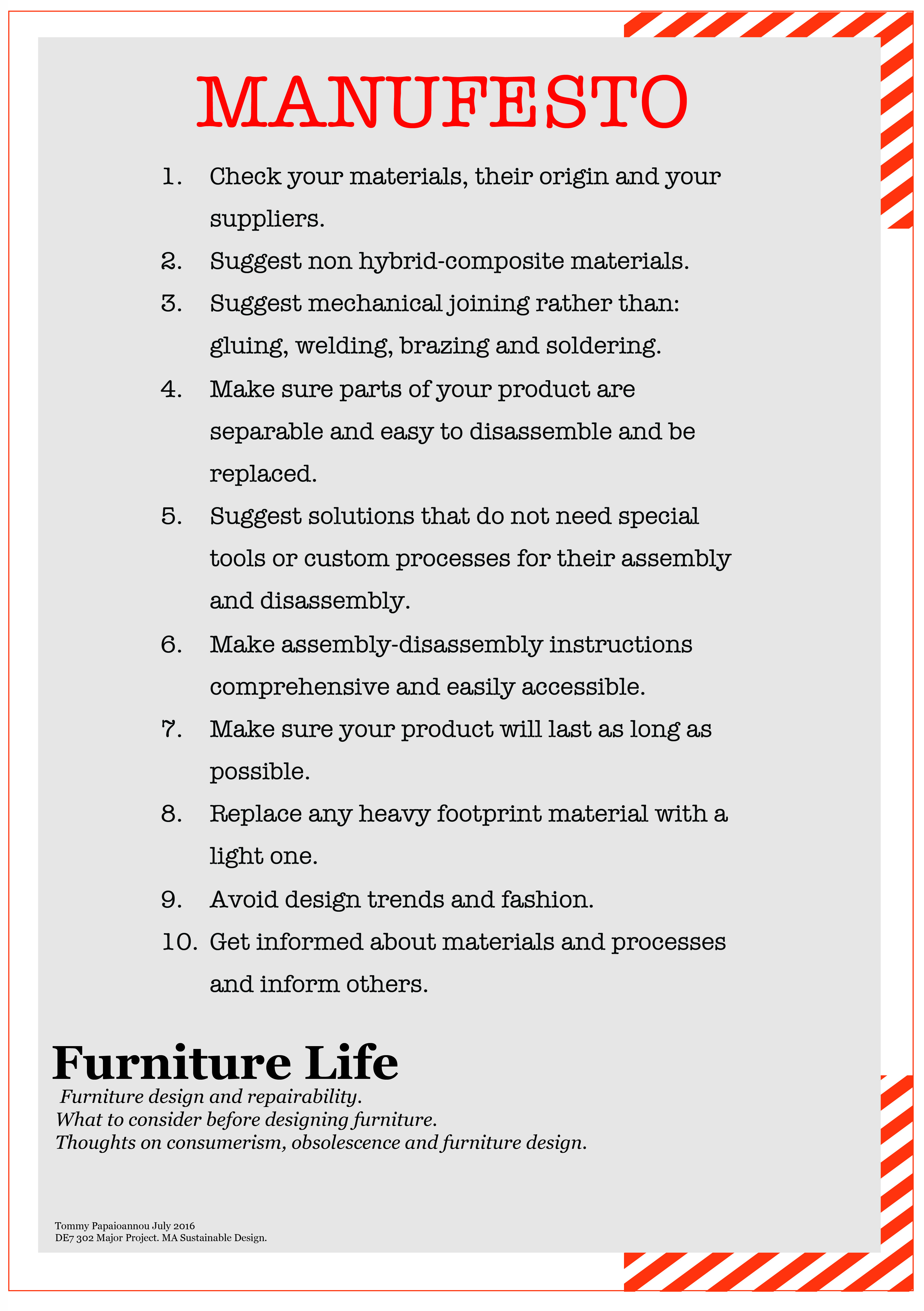

To summarise the thoughts and the suggestions of this research 10 recommendations have been developed and a manifesto has been produced. This is to act as a general guide for furniture designers. Wanting to keep it short and sharp it is generic and not analytical (like most manifestos are). Please note that these suggestions are the result of this research as well as part of years of personal experience.

A short analysis of each point follows bellow to assist towards a better understanding. It has been named MANUFESTO signposting that repairing is a manual process/practice.

- Check your materials, their origin and your suppliers.

There are unsustainable sources and practices in the global supplying chain of prime materials. Usually certification and accreditation gives a good indication of origin and practise. Local sourcing is ideal. Very low prices are usually an indication of low quality, hidden costs and bad practises.

- Suggest non hybrid-composite materials.

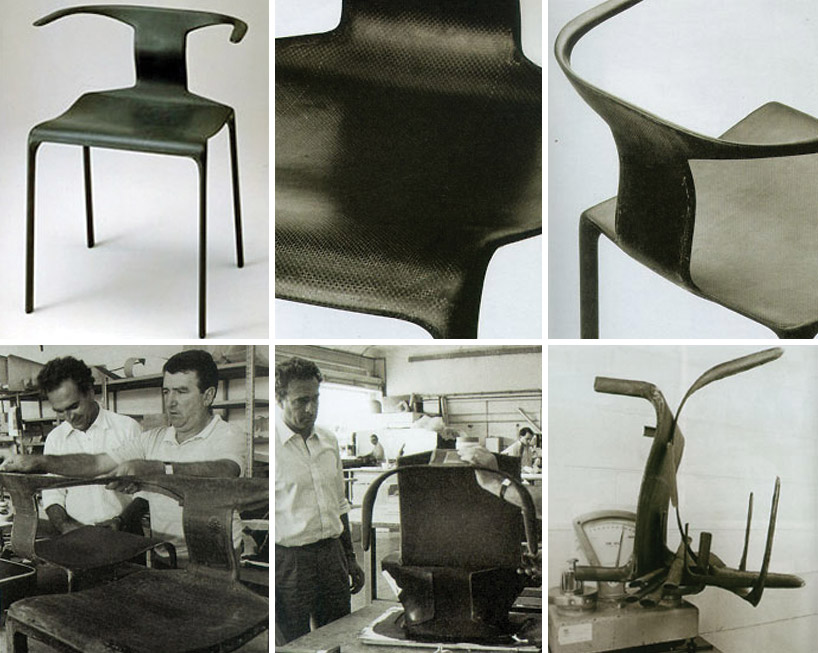

Reinforcing two or more materials of varying properties forms composite or hybrid materials. Hybridisation is a process of incorporating synthetic fibers with that of natural and metallic fibers in order to yield better strength, stiffness, high strength to weight ratio and other mechanical properties. Composites can offer a series of advantages (especially light weight and strength) but are extremely hard to take apart and reprocess for recycling or reuse. Usually they are petrochemically based and are highly toxic and unsustainable.

- Suggest mechanical joining rather than: gluing, welding, brazing and soldering.

Gluing and welding is a fast, cheap and very effective way of putting together two separate parts or materials. It makes it impossible to take these elements apart for repairs. It seems impossible but there is a variety of examples of how to put together different parts using mechanical means without problems. Cars, boats, motorbikes, airplanes etc are all assembled with mechanical joints and fasteners. They carry heavy weights and are subject to massive physical forces. They all function and operate sound and safely as long as they are serviced accordingly

4.Make sure parts of your product are separable and easy to disassemble and be replaced.

Ease of disassembly has a cost effect and that can be key to whether repair will take place or not.

5. Suggest solutions that do not need special tools or custom processes for their assembly and disassembly.

Special tools and processes function as disincentives for people. Ideally a user should be able to replace a part without going to specialists using everyday tools.

- Make assembly-disassembly instructions comprehensive and easily accessible.

It is essential for instructions to be comprehensive to the average user and widely accessible via Internet.

- Make sure your product will last as long as possible.

Products were made this way for thousands of years. This is a matter of prime materials quality and manufacturing processes. It adds cost on the product but it can be seen as an investment. Quality furniture has a very high resale price.

- Replace any heavy footprint material with a light one.

Traditional materials have a lower environmental impact. A life cycle assessment of materials gives a very good picture of their impact. An organisation like the Materials Council can help designers being informed. See image of materials footprint.

- Avoid design trends and fashion.

As professor Tim Cooper argues in his ‘Longer Lasting Products’ book: today’s fashion is tomorrow’s junk. Today’s functionality is tomorrow’s dysfunctionality. Today’s beauty is tomorrow’s tawdry reject.

- Get informed about materials and processes and inform others.

It is essential to be and stay informed about materials and processes. It is a big part of any designer’s job. Developments and research results are in a constant motion getting updated and introducing new insights and results all the time. Spreading the word is essential for every conscious designer.